Andrew Sung Taek Ingersoll

Breathing House

Sept 10 - Oct 14, 2023

620 Kearny St.

Reception: Sunday, September 10 2-5pm

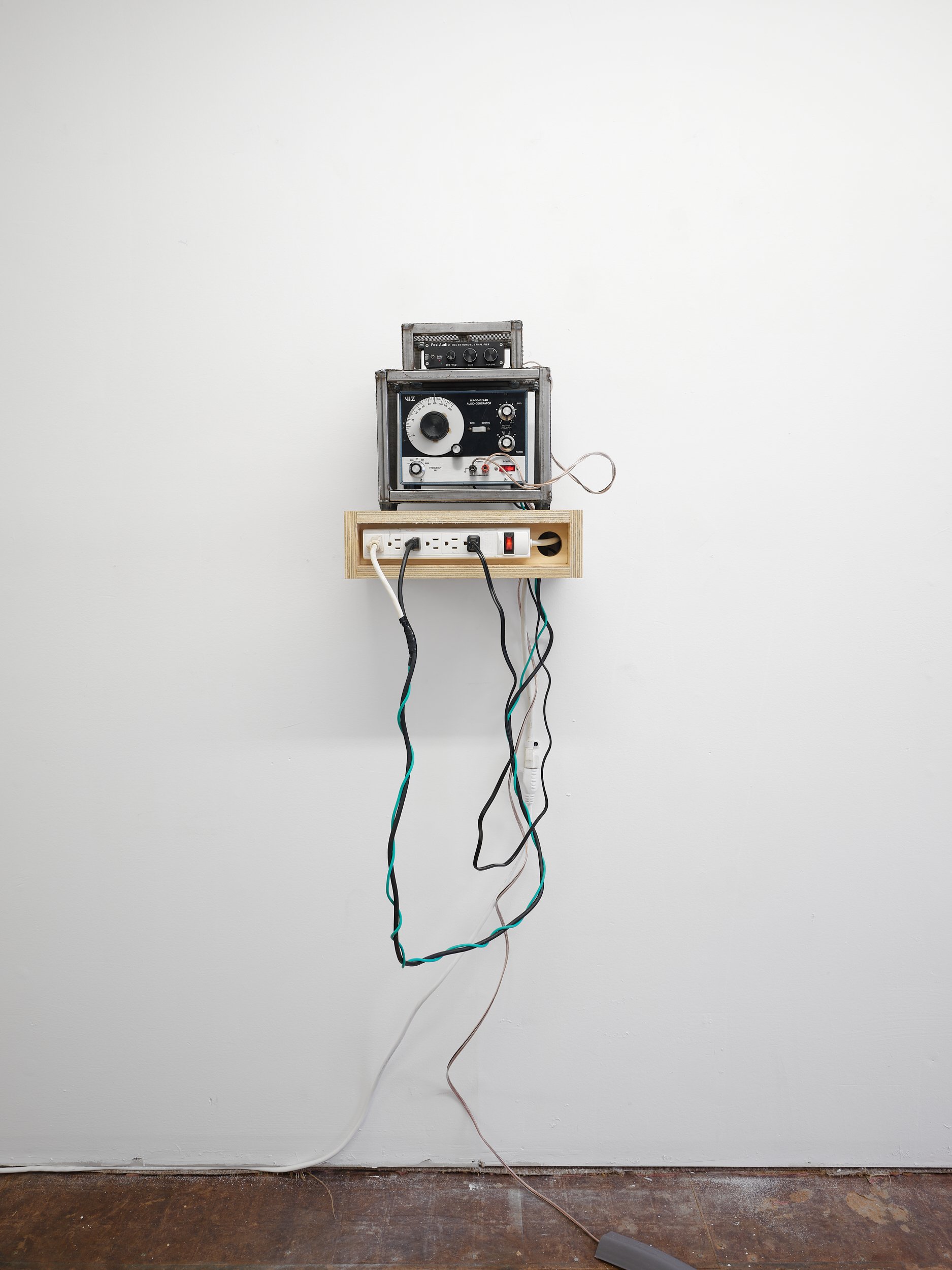

Andrew Sung Taek Ingersoll, Humming Pipe, 2023

Bathroom sink, modified wooden cabinet, modified chrome plated s-pipe, 12” subwoofer, plumbers tape, screws, 1991 Honda civic hood prop, liquid nails, custom steel hardware, plexiglass, vintage signal generator, amplifier, wire

Strewn about both floors of Et al. are families of gutted objects by Andrew Sung Taek Ingersoll. Found and modified, their bodies now realize a capacity to articulate the energy that courses through their form. Synapses fire as spectacle.

In Breathing House, Ingersoll’s asynchronous tapping chairs puncture through the low, droning hum of his rice-cookers-turned-speakers. Punctums perpetually flicker anew within an otherwise still, crooning studium. Severed are the chairs’ legs (only one each) and agape are the mouths of multipurpose appliances. Carrying psychosocial associations of domesticity and perseverance, they never cease to sound.

Upon looking at—and hearing—Ingersoll’s objects, I’m reminded of Jane Bennett’s phenomenological account of experiencing detritus, her witnessing of “the power and entanglement of objects that gave rise to a nameless awareness of the impossible singularity of objects.” “Nameless” subsequently became “vital materialism,” and the discreteness of object, subject, and phenomena collapsed into an affair of mutual constitution, according to the political theorist. I think of this when I think of what an object is beneath the skin, and how we will always end up finding ourselves intertwined within its sinews. I can’t escape my father's wristwatch, and perhaps Ingersoll can’t escape his.

Andrew’s objects are anchored in ontologies all their own. Yes, their form and status have been shaped around particular utilitarian affordances, but their raison d’être is outside of us. Andrew's objects don’t perform, they instead make it known they’re breathing alongside you.

✽

I miss my grandmother. When she died from suffocation and the first American home she moved into 55 years ago had its intestines spilled out on the floor before me I became possessive. I felt the indomitable urge to salvage every residual particle of a life lived. In the absence of her body, furniture took on new shapes and no longer did surfaces feel cold. She was breathing in everything; yes, I felt it in the bed of my deepest chasm that her soft, stuttering voice murmured from the things her skin warmed up the most. And I sometimes listen for that voice in begging women around the Mexicali border.

Expanding ribcages.

Clicking tongues.

A breathing house.

-Mara Hassan

Citation: Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London: Duke University Press.